Russell Lee: New Mexico Homesteaders in Pie Town

By Arthur H. Bleich

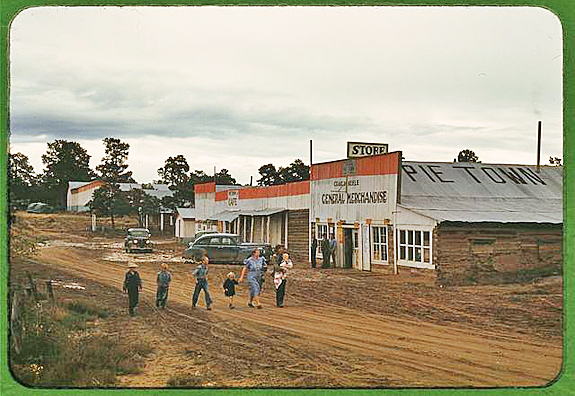

On June 6, 1940 photographer Russell Lee drove into Pie Town, New Mexico, a scattering of frontier buildings straddling dusty Route 60 and perched a mile-and-a-half high on the Continental Divide .

The Magdalena News, published 65 miles away (and delivered daily by motor stage) confirmed that “Mr. Lee of Dallas, Texas, is staying in Pie Town, taking pictures of most anything he can find. Mr. Lee is a photographer for the United States Department of Agriculture.”

Pie Town, New Mexico.

Working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), Lee’s job was to photograph the government’s efforts to lift Americans out of the Great Depression. He’d been criss-crossing the country for four years shooting in rural areas, small towns and cities before arriving in Pie Town to document life there. The town’s name intrigued him. Residents explained that an early settler baked delicious pies as desserts for cowboys, who sometimes ate at his general store. In time, the crossroads where the store sat was called “the pie town.”

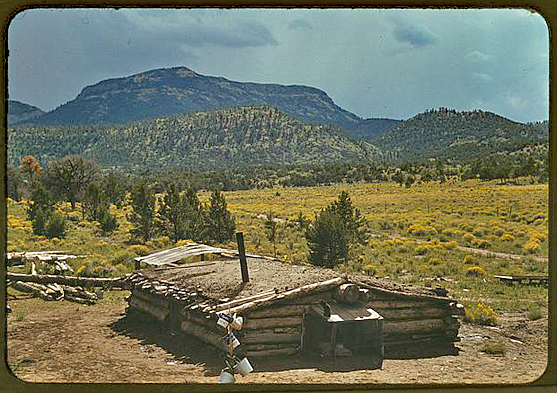

Dugout house of Faro Caudill, homesteader with Mt. Allegro in the background, Pie Town, New Mexico.

Born in Ottawa, IL, in 1903, Lee was 22 when he graduated from college with a degree in chemical engineering. He went to work as a chemist in a factory, but was restless. Luckily, an inheritance offered him freedom. He married painter Doris Emrick in 1927, quit his job soon after and became immersed in the art world. He tried painting, but it was not to be. “I realized that I couldn’t be a very good painter,” he conceded, “because I couldn’t draw very well.”

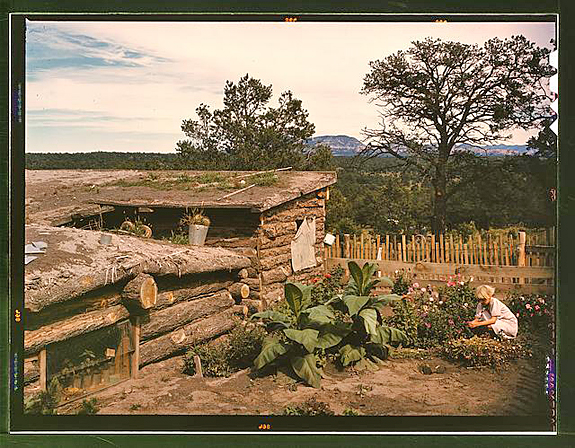

Garden adjacent to the dugout home of Jack Whinery, homesteader, Pie Town, New Mexico.

He and Doris summered at an artist’s colony in Woodstock, NY, and wintered in New York City. He found his medium of artistic expression in 1935 when he bought his first Contax 35mm camera amd threw himself into photography. “I went to auctions where poor people were selling off all their household goods. I went to a local election and photographed it using the Contax and open flash… I tried my hand at a county fair. That spring I went down to Pennsylvania with some friends and photographed the bootleg coal miners, I was developing a social conscience at that time because people were so damned poor.”

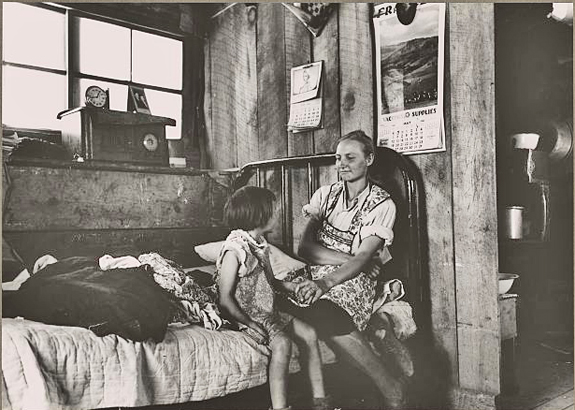

Mrs. Caudill and her daughter in their dugout, Pie Town, New Mexico. The Caudills have one of the few radios in their neighborhood, and many farmers and their families visit the Caudills on winter nights to listen to music and news and play “Forty Two.”

That social conscience, coupled with an impressive portfolio landed him a job with the FSA, who was resettling farmers whose land had been ravaged by drought and dust storms. After shooting a trial project at a New Jersey housing project in 1936, Lee was invited to join a star-studded staff that included Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein and Walker Evans. For the next six years he was on the road documenting life in 30 states. He eventually became the FSA’s most prolific photographer, shooting nearly a third of the agency’s 63,000 captioned images.

Mr. and Mrs. Jack Whinery and their five children in their dugout. Pie Town, New Mexico. Mr. Whinery had worked on farms in Texas for wages until homesteading one year ago. He arrived in Pie Town with thirty cents which he spent for nails to build his dugout. He donates his services as a preacher to the church.

On one trip, Lee covered the great floods of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, which had disrupted the lives of thousands of people who lived along their banks. Once an old lady asked him why he wanted to take her picture. Lee replied: “Lady, you’re having a hard time and a lot of people don’t think you’re having such a hard time. We want to show them that you’re a human being, a nice human being, but you’re having troubles.” She agreed and invited him to lunch. He had a folksy way with people that was unique.

Lee and Doris divorced in 1939. He then married Jean Smith, a newspaper reporter he’d met in New Orleans. She became a great asset to Lee—accompanying him on most of his assignments, writing short essays, captioning pictures and breaking the ice with subjects sometimes suspicious of the government’s motives.

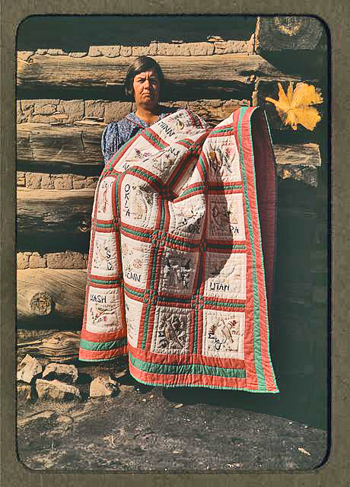

Mrs. Bill Stagg with state quilt which she made, Pie Town, New Mexico.

The residents of Pie Town—about 200 families—were more curious than suspicious. They had been blown out of the dustbowls of Texas and Oklahoma and given one of the last opportunities in the country to homestead sparse but stunningly beautiful land in the west-central part of the state. They welcomed Lee’s efforts to show what they had accomplished in the face of bone-chilling winters, scorching summers and a scarcity of water.

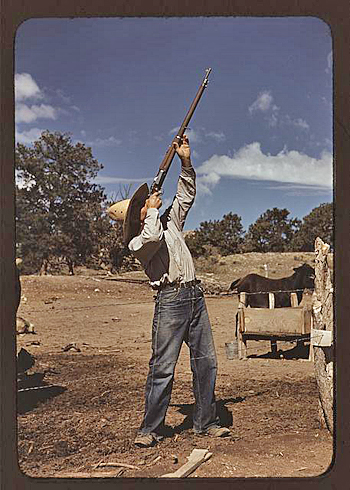

Mr. Leatherman, homesteader, shooting hawks which have been carrying away his chickens.

The town had few amenities; no doctors, dentists, phones, electricity or running water. A short growing season meant many settlers couldn’t spare time to build proper houses; they lived in dugouts—cellars over which they threw a primitive roof. But they had built a post office, church, school, general store and a small hotel. Arriving for a three-week stay with the trunk of their 1938 Chevy chock full of cameras, film, flashbulbs and other photographic gear, Lee and Jean immediately rented all three of the hotel’s rooms, converting one into a darkroom for developing negatives.

Lee’s cameras of choice were 35mm, but he also used a 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 Super Ikonta B folding camera and a 4 x 5 view camera, which required a tripod. A 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 press camera fitted with a synchronized flash gun was a must for scenes that couldn’t be captured by available light on the slow (ASA/ISO 32) films of the day. He shot mostly in B&W but also captured some priceless images in color which was even slower (ASA/ISO 10).

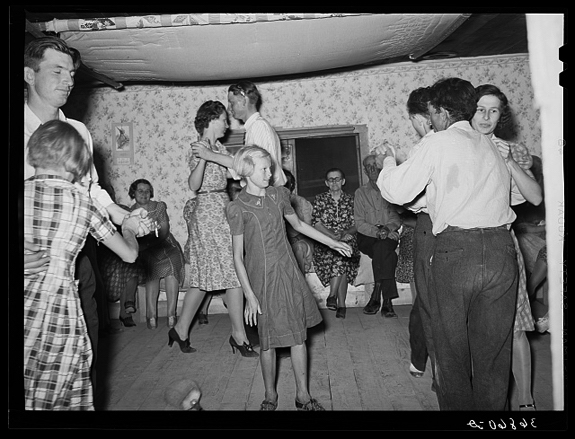

The broom dance at the square dance. Pie Town, New Mexico. The extra girl or man dances around with a broom for a partner. Then drops broom loudly; everyone must change partners and the one left out in the exchange must then dance with the broom.

But he had not totally mastered flash technique and shot many of his images with flash on the camera, resulting in harsh lighting and heavy shadows. He was somewhat defensive when asked about that. “I have always believed in keeping my technique as simple as possible in the field,” he would explain. “If I had begun to string wires for multiple flash exposures, I would have lost many important pictures.” But once Jean was along to help, he began to use more off-camera and multiple flashes with better results.

Though Lee was adept at documenting adversity, he also relished shooting the good times that hard times spawn—all-day church sings, picnics, dances, band concerts, holiday celebrations and even people having fun at bars and nightclubs. These images show the indomitable American spirit as folks all over the country began to recover and regain their self-esteem. But Pie Town was a sad exception; a long, dry spell withered crops and the town was in decline by the 1950s. Today, only a few buildings remain, one of which is the Daily Pie Café that still bakes tasty pies relished by tourists.

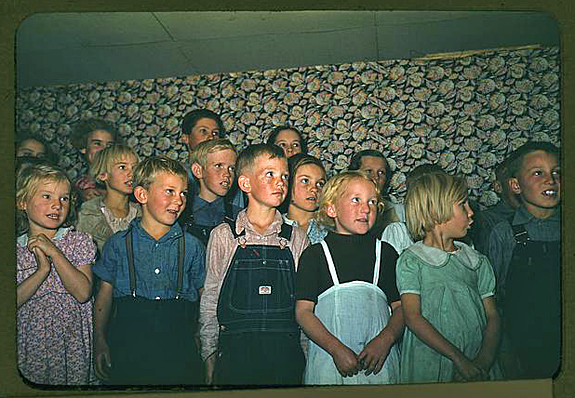

School children singing, Pie Town, New Mexico.

As World War II loomed, the FSA folded into the Office of War Information and one of Lee’s assignments was to document the relocation of West Coast Japanese-Americans to inland camps. In 1942, he was tapped by the Air Transport Command to do aerial photography throughout the world to provide American military pilots with visual briefing photos.

When the war ended, Lee shot a project for Department of the Interior on coal mining and worked on assignments for Fortune Magazine and major oil companies. He also documented the lives of Spanish-speaking people in the Southwest, covered the Kennedy-Johnson campaign for The New York Times and created a series of touching images of life in Italy during a summer there.

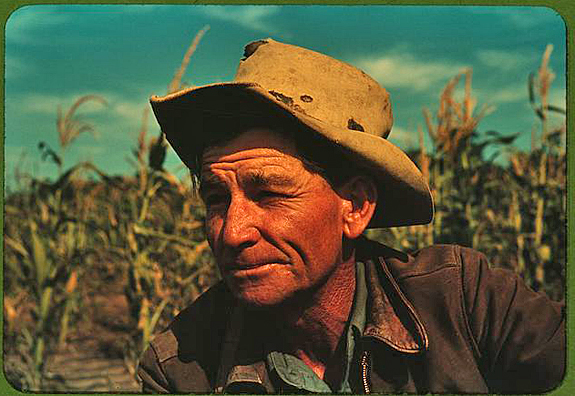

Jim Norris, homesteader, Pie Town, New Mexico.

Yet for all his achievements as a photographer, Lee had a great talent for teaching. For 13 years, beginning in 1949, he was an instructor and then director of the University of Missouri’s annual Photo Workshop. In 1965 he was invited to teach photography as a faculty member of the Art Department at the University of Texas at Austin, a post he held until he retired in 1973.

Russell Lee died of bone cancer in 1986, leaving behind a legacy of thousands of documentary images showing the heart of America and hundreds of dedicated students trained to carry on his vision.

RESOURCES:

Russell Lee’s entire body of work is viewable in the FSA/OWI files at: https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsowhome.html

All images are in the Public Domain and are downloadable in a variety of resolutions at no charge.

All images and captions by Russell Lee.

Original Publication Date: July 18, 2023

Article Last updated: July 13, 2024

Please log in to leave a comment.

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Newsletters

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

June, 2024

May, 2024

April, 2024

March, 2024

February, 2024

January, 2024

December, 2023

November, 2023

October, 2023

more archive dates

archive article list